Another response to James.

I was going to respond a couple of nights ago, but then my response ended up being half a dissertation and I saved it as a draft at my blog instead. Sometimes being able to easily jump from box to box means that you’re less likely to stay in one to make a, um, concerted point.

I guess that’s always the problem with authoritative statements about something relative–they turn back on themselves. But the nice thing about that is that it means you know you’re getting to the limits of the box and have to step out of it to see it from a different vantage point.

See, the other reason I didn’t respond was because of this:

To really live your life like that– not just adopt such a position in a drunken argument at a loud party– I think would be quite difficult.

Because I seriously starting thinking about all the performance art, phonetic poetry, noise music, experimental film/video, sound installations, multi-media performances, etc, etc…ad nauseum that I’ve been doing the past ten years and realized how easy it is to fall into the box that lets you talk about (i.e. critique) post-modernity without actually having lived it.

It always tickles me when reading academic (or pseudo-academic) pomo crit of things–to go back to the idea of “Death-of-the-author-as-result-of-Western-Critical-mindset”–because those types of text just bring to mind the cliched armchair critic that wouldn’t likely know the first thing about doing some of the activities that are the object of his criticism.

See, there’s a common saying in Thailand: “Kohn roo mai poot; kohn poot mai roo” (and this is actually just a restatement from the Daode jing), that translates (quite straightforwardly) as “The one who knows doesn’t speak; the one who speaks doesn’t know.” Timothy Hoare, in his book about the Thai dance-drama form Khon, writes about the phrase for some length (and yeah, it is ironic that he writes about it at all):

Even in the Thai language, reliable literary works on Khon are minimal, for the discursive habit of producing meticulous documentation that is grounded in a long and careful process of research has simply not been a traditional aspect of the Thai academic/historical consciousness. Appropriately, Khon provides us with a prime example of how this is so. In Thai education overall, the familiar euphemism, “Those who can’t do, teach,” has no meaning. Quite the contrary in the case of Khon, a teacher of Khon is an accomplished practitioner of Khon. He/she is respected for his/her ability, experience and knowledge as a performer and living vessel of the tradition, not as a “scholar” in the Western sense of the term.

…

Consequently, if it is deemed necessary for an arts institution to compile and publish a new text under its own authority, it is usually not the teacher–the one with expertise–who is commisioned to author it, but someone from “the outside,”…who knows the artform as “a layperson.” The result is usaully sketchy, sometimes inaccurate and, at best, suitable for the tourist who wants nothing more than a superficial treatment.

Setting aside some of the Orientalisms in the quote I gave, there’s a Buddhist saying, “mistaking the finger that is pointing at the moon for the moon itself,” that captures the idea that Hoare is stating rather succinctly.

I especially love reading critiques of Asian cinema, particularly “martial arts” flicks. Since a number of comics bloggers had so much to say about Ron Rosenbaum’s anti-Kill Bill/Sin City piece a while back, I’ll use it as an example (with some Saidean interpretive glosses in brackets):

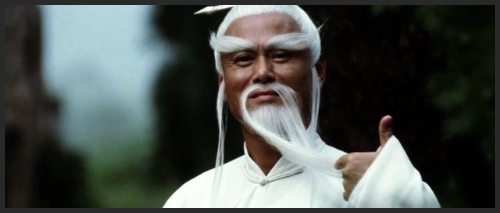

Or maybe you were too busy laughing yourself silly over the single most ridiculous beard in the history of cinema [which just happens to be precisely one of the types of hu hsu (“beards”) as it has appeared in decades of Chinese Cinema and centuries in traditional Chinese Opera], the one on “Master Pai Mei,” who we’re supposed to believe is the ultimate extra-special, wise-beyond-Yoda spiritual warrior [because obviously the wu lao sheng character, as expertly performed by Gordon Liu, in traditional Chinese Opera and Chinese wuxia pian Cinema warrants immediate derision and dismissal]. You know, the laughable Orientalist caricature [because surely Ron knows a “real Oriental character” from a “laughable Orientalist caricature”] who teaches Uma Thurman the super-secret, way-forbidden “Exploding Heart” punch with which she finally kills Bill?

Point is, each and every movement (not just the spoken text) that Gordon Liu performed has a meaning. Each and every piece of clothing and the beard and hairstyle that Gordon Liu sports have meanings. Even each specific movement of the beard that Gordon Liu performs has a meaning. But most of that is lost on an audience unfamiliar with the ersatz language of Chinese cinema and Chinese Opera.

But the dismissiveness and derision that is relatively commonplace in criticisms of either Asian MA films or films inspired and heavily borrowing from Asian MA film conventions iare premised on a box that doesn’t have nearly as much to do about the genres as some would like to believe. Would we criticize a composition in Sign Language like this? Would we say that “talkies” are just an adult version of or reference to infant’s “babble-talk?” I’m still actually surprised that I haven’t come across a review of Kill Bill that mentions the fact that Beatrix doesn’t actually kill anyone in vol. 2.

I don’t think it’s at all controversial to state that kung fu flicks rely heavily on Chinese Opera traditions and conventions (hell, even Chinese comics do), but the “Death of the Author” idea is just one aspect of what I’m coming to call textually driven criticism.

See–this is also why I didn’t post before–going off on tangents are so much easier when you’re used to jumping boxes.

Dave Fiore is fun, even when he’s going off into what linguist, Ray Jackendoff, calls the “Western bias of non-linguistic” thought. “We don’t know something until we try to say it.” “We communicate stories through narratives.” (my bad paraphrases of things Dave has stated). It doesn’t seem like many people realize how fuzzy the boundaries between different forms of communication or human interaction can be while they are [ironically] stating, unequivocably, that language is ambiguous.

What’s the difference between music and languages that use lexical tones to differentiate between meanings?

What’s the difference between the highly formalized gestures of Asian dance-dramas and the gestures of Sign Language?

What’s the difference between writing visual graphemes (i.e. “text”) and drawing visual logographs, pictographs, comics, or writing mathematical ideograms, and musical notation?

I’ve always said (partly because it’s so damn clever) that the last person you ask about a piece of art is the guy what made it. In truth, what he has to say about a work in question may be interesting, but I don’t have to believe him if I don’t want to.

See, that’s where textually driven criticsm has gotten in the way of the idea of an intentional object. Why does intention have to be bound in what an author says about her work? Why can it not be bound in the work itself? In other words–going back to mistaking the finger pointing for the moon itself–an author that makes a statement about her intention of a work is already different a different matter than the actual intention that the work itself was meant to communicate. If you say (or rather type) to me:

(A) “You’re an ass!”

and then

(B) explain to me:

“What I intended by (A) is (C).”

What seems to be really going on here is that (C) is your interpretation of (A) “You’re an ass!”

(C) is pointing to (A) like the finger to the moon. An author’s intention need not be considered unrecoverable when all we’re doing is looking at an author’s comment (C) about (A). Look at (A) if you want to find the intention.

The “perfect” act of communication I mentioned in that other comment is precisely the utterance of (A), not the explanation (B) or the “interpretation” (C).

I don’t think statements in the form of “all acts of communication have a diffusive quality” at all gets close to articulating these types of differences that I’m making. Indeed, these types of statements are constructed from within a box that makes them very improbable (or at least unacceptable). Obviously, critics can just reject my box, or any other box for that matter just as they can reject Chinese jingju conventions and talk about the laughable beard of Pai Mei, or just call people “stupid fucks” for that matter. Doesn’t change the [provisional] fact that these critics can’t make (or choose not to make) distinctions that others can.

This is sort of what I meant by choosing to acquire the skill to play the Dvořák Cello Concerto rather than implicitly blaming the piece (or the composer/author) for it’s “essential” difficulty. The Dvořák’s purported “difficulty” is just the reader’s commentary on her own relation to the text. In other words:

She be explainin’ (or (B)) through (C) her relationship to (A) rather than changing her relationship to (A) by acquiring skill.

I guess that’s also another Buddhist aspect of one of my boxes–the “Nagarjunian” idea of upaya-kausalya (“skillfull means”), that is. Damn me for being raised Theravada Buddhist I suppose.

Don’t ask the person, because he’ll just give you an interpretation of his intention. The actual intention is bound up in the “utterance” of the intentional object–which can also be some type of performative act like a statement. In other words, Kohn roo mai poot; kohn poot mai roo na krop.

That last makes a sort of sense given this context, since we’re basically analyzing and criticizing criticism after all. And by all means, more pics of guys in lingerie!

*note that this is a very abbreviated/cut-n-pasted version of the comment I was going to post. Maybe you’ll be thankful for this fact after you’ve read through my self-indulgent post. heh.

_________________________

originally posted here as “response to James 3.5”:

http://silpayamanant.blogspot.com/2005/09/response-to-james-pt-35_26.html

Posted before I have the sense to stop myself:

You’ll have to forgive me here– I was never all that smart, and I currently have half a bottle of crap shiraz in me, so I don’t even know if this will all be in English.

Don’t ask the person, because he’ll just give you an interpretation of his intention. The actual intention is bound up in the “utterance” of the intentional object–

I’m a little unclear here, because it seems like you’re agreeing with my idea of ‘never trust the artist.’ But maybe saying there’s a different reason for not trusting him? Or at least not relying on him?

(You notice, I notice, the mailman notices, that you generally use “her” as your hypothetical artist– except when you forget– and I use “him.” Hmm. I could write a book. It would make no sense, but me and one drunk Australian would find it fascinating. Anyway.)

What I’m saying is that it seems like the paragraph I quote here comes to the same destination via different route that the “death of the author” guys travel. Please clarify for me.

The first blog post I wrote– which I eventually trashed– was about how Dave Fiore is probably the only post-modernist I’ve seen who seems to walk the walk. I’m sure there are others, but I don’t get out much.

I’m surprised, actually, that all the things you do, Jon, are not the work of a post-modernist.

I have a theory– well, I have a theory on pretty much everything, don’t I? The ability to talk shit about literally any topic is possibly the greatest benefit of a liberal arts education. HOWEVER, relevant to the topic at hand, I have a theory on critics, that I’ve meant to go into for a while. I believe critics are actually people who love an artform too much to be able to confine themselves to actually making it. I find the “those who can, do” formulation too easy.

Trying to be brief: you take a shine to some creative form(s) of communication, and decide to learn the ropes, and then apply them. Ten years later, you’re a full fledged starving artist. Let’s take film. I think film critics are actually people who love movies so goddamn much that they would rather spend their time consuming as many movies as possible, rather than just making a few. For a man who just absolutely loves movies, what’s better? Making 2 a year? Or watching a hundred? I think you can only be a real critic if you love a given form so much you are possessed of the (completely insatiable, slightly irrational) desire to consume all of it. Which explains for me why critics get so mad when a piece of work sucks– it’s like the entire art form reared up and spat at them. Imagine the man or woman you’ve loved your whole life cheating on you with the wife-beating slope-browed troglodyte next door. Fucking hurts, don’t it?

I must confess to my love of theatrics and the declaritive (not “authoritative,” please, I beg you).

Kill Bill is problematic. There’s way too many things going on not just in the movie, but around it. The things you’re saying about Gordon Liu’s performance are interesting because, of course, I would never have known about those historical influences. But then, I question if Tarantino knew. And so here I am putting all the weight on the author, regardless of the final text (or is Liu the author of his performance? or how about I just smash a hammer on my foot right now and complete the circle of pain and confusion I’ve started?). Meanwhile, here you are telling me that the text– the film– is where it’s at; nevermind whether Tarantino knew those movements had meanings, those meanings are committed to celluloid and are part of the final document, so they’re valid.

The real problem with Kill Bill isn’t the movie, but the polarizing effect of Tarantino. And thus I shall leave it, lest I go off on another tangent.

What’s the difference between music and languages that use lexical tones to differentiate between meanings?

Specificity?

Oh, wait, was that rhetorical? The differences are important, man. They’re what make you choose paint over clay, or dance over comedy (can we make stand-up the “tenth art,” please? I fucking love stand-up; blue collar jazz, motherfucker).

I’m coming up short with a decent analogy, so I’ll try to hash it out like an adult here. I think communication is a basic human drive, like sex and sleep and eating. And all the things we do, including cooking and fucking, are variations on the attempt to “speak” to other people. So there’s going to be fuzzy lines between forms, yeah, because all the forms are essentially trying to do the same thing.

What I can’t do, or don’t want to do (and why not? am I just too hidebound to try it another way?), is speak of a given work as an independent object. I can’t talk about The Book, I have to talk about the book as uniquely constrained interface between Reader and Author.

Watch this. I can get really annoying and say that your different approach, rather than being wrong, is simply you, a Reader, “interfacing” with the Author in a completely different way than I. Much the same way two readers interpret a single text differently.

You see what I did there? I went all po-mo on your ass, even though that shit gives me the hives. How fucked is that? It’s such a useful tool, I must admit, to make argument pointless. It’s like the Academy’s variation on the schoolyard trick of repeating everything you say till you get frustrated and walk away (that’s how it works on me, anyway).

You want to know what my blog is all about? Of course you do, what else could you possibly have to do with your life? My blog is me trying to figure out how all this shit works, in public, so that people like you will laugh at me and tell me my zipper’s open.

I will end with a thought that really only just popped into my head today: artists misunderstand critics far more often than the reverse.

LikeLike

Just in case you didn’t notice, I posted a response as a regular blog post–I forgot about the damn no “blockquote” tag thing in comments and was too lazy to go back and change them all.Here it is

LikeLike

I was going to say something, then I read the comment by James and everything you said seems to have escaped my brain. @James BEST DRUNKEN COMMENT EVER.

The Dvořák’s purported “difficulty” is just the reader’s commentary on her own relation to the text. Love love love this! Yeah, three loves. Somehow the way you said that made things so clear. Not just in music, but in life. Like it just connected about a billion previously unconnected things in my head. I feel like I’ve heard the same idea a million times before, but until you phrased it that way I never truly understood it.

I had more to say, but Mr. Drunken Commenter drove it from me and it hasn’t come back. Perhaps more on another day.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed the discussions James and I had during that time. I guess it’s pretty obvious that I’ve imported some of my other blogs into this one–this post was over at the previous Mae Mai which was more of a comics/arts criticism blog.

James cracks me up, though he’s since taken his blog down and deleted the whole thing.

I guess I’ve always felt that way about things–we don’t understand or comprehend things so much as we are in some sort of relationship with things–if we change, then our relationship to things change.

If I practice enough, then I will have changed myself enough so that my relationship to the Dvořák concerto is no longer one where I see it as “difficult.”

Same thing with everything else, really–!

LikeLike

Ok, James’ response has been formatted to match how he posted it in the original entry: http://silpayamanant.blogspot.com/2005/09/response-to-james-pt-35_26.html

LikeLike