In my previous post I talked about the Choreography of the Mouth when learning how to sing in multiple langauges and mentioned I would post about Music as Choreography. Here is that post. As I said previously:

It’s simply about the choreography of the mouth (my next post will talk about Music as Choreography) which is really no different than the choreography of any other part of the body. You move or you manipulate your body in various ways to make a sound. Sometimes that sound comes from your body (e.g. your voice), and sometimes that sounds comes from some external device that your body is interacting with (e.g. musical instrument).

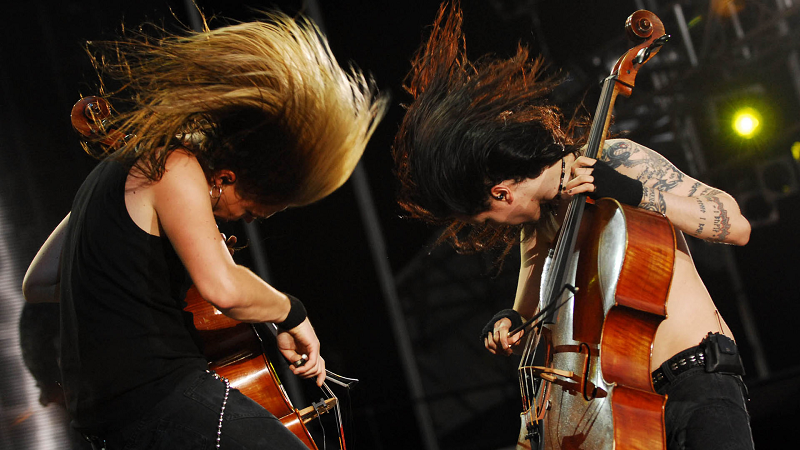

Obviously there’s a difference between being, say, a musical act with a choreographed or semi-choreographed stage show and a performance that was designed as a theatrical piece. In the end, the difference isn’t much more than the level and difficulty of “precomposed” choreography. Whether you’re putting on a rock show and headbanging (e.g. Apocalyptica) or running around the stage (e.g. the late Mike Edwards of ELO), it still involves some kind of choreography–even if that is just spontaneous and improvised choreography.

The stage shows of rock and pop type events, however, are usually subsidiary to the music. Unless the level of staging involves the heavy usage of props, extras, pyrotechnics, and other multi-media effects (I’m thinking of, e.g., Iron Maiden, Dio, Judas Priest here) then the music is really the primary focus in ways that it would be secondary for shows put on by Cirque du Soliel, Stomp, and the Blue Man Group.

At a more modest level than these huge stadium concert productions we find the choreography done by the cellist dancers I mentioned in my previous post which are more akin to modern dance performances than either the stadium rock or multi-media shows above. Here’s where Marston Smith, the Lord of the Cello, stands somewhere in between. Here’s a video of his “Pavane” an imaginative take setting a story (involving freeing a vampire/demon from chains by the sounds of his cello) to a re-working of Gabriel Fauré’s “Pavane”:

This is similar to the work I mentioned doing with Secondhand in the first post in this series. The cello is an integral part of the actual narrative and there is actually a narrative. So the cello doesn’t get used simply as a prop in the dance, or as an abstract musical instrument occasionally making music or sounds during the dance. This is also how the Musictelling troupe, Tales & Scales, approaches their productions. In many ways, this is one of the easiest ways to integrate non-musical choreography while playing an instrument, since it involves using the instrument AS and instrument in the service of the narrative. In other words, the main difficulties lay in being able to move around with an instrument traditionally held while in a stationary position a fact that is lampooned in the 1969 Woody Allen Mockumentary, Take the Money and Run:

As well as in one of the most recent The Piano Guys video, Mission Impossible with wonderful cellist, Stephen Sharp Nelson, and violinist, Lindsey Stirling:

Of course the MOB (Marching Owl Band) Strings at Rice University have solved the problem with special cello harnesses:

As has this Princeton alum:

So obviously the first obstacle for dancing with the cello is to get past only being able to be in a sitting position while playing. I remember when I was younger doing “stupid cello tricks” like playing the instrument in my lap or laying on my back on the floor and playing it that way. I also often stand while playing (which I absolutely abhor doing), as I related in the first post in this series. From there it’s a simple step from, well, taking that first dance step while playing. Having some sort of harness as many of the above-mentioned cellists do can be immensely helpful, but not necessary.

I did my first dance/cello piece with the endpin fully extended (fortunately for me, fully extended is just enough to stand while playing comfortably) and many of the cellist/dancers in the previous post use standard acoustic cellos for their very involved dance work with the instrument (though, as I mentioned, the cello is as much a prop in service of the dance as it is an instrument to be played while dancing).

The second, and probably bigger obstacle, is getting yourself outside of the idea that normal music-making is anything more than a type of choreography and starting to think of choreography that has a visual effect instead of, or in addition to, an aural effect.

The third obstacle is deciding what role the instrument has in the choreography. Is it primarily a prop? Is it an integral part of the narrative as a musical instrument? Is is the focus of the performance which is accented by movement to complement the primarily musical performance? These are some of the questions I’ll address more in future installments of this blogpost series.

________________________

RELATED POSTS

For more posts in Singing and Dancing while Playing the Cello, please visit this link.

Check out “Tales and Scales”

LikeLike

Yes, I mention them in the post above as well as in the previous post. I almost auditioned with them back in ’96 after their cellist left!

LikeLike

Oops – I should read more carefully before commenting. Personally I am not a fine of the dancing and playing schtick, at least from what I’ve seen of Tales and Scales doing it. For one thing, playing well is difficult, and encourages lip-syncing to recordings which is largely what Piano Guys, Blue Man Group, etc. rely on. (Blue Man Group mixes in some live playing, too, but much is pure visual.)

LikeLike

No worries, Raymond. And you hit on one of the real difficulties of heavily choreographed performances–the tendency to lip/play synch to pre-recorded materials. Obviously for film and video, this is almost necessary since you’re likely to have several takes/angles for the final production so synching to one [pre-recorded] audio is far more useful than trying to edit a ton of different live audio takes which just may not synch up together well.

For the live productions, it can take a pretty big (and ultimately expensive) crew to deal with the live sound (if amplified) otherwise the rehearsal time required is going to be immense since you’re obviously dealing with both music and dance. And in the end, the more difficult one or the other is, the more time it will take to put together–and time constraints can be an impediment for making this kind of performance a normal thing.

LikeLike

This is really cool … shows you what my instincts are as a pianist that I never realized how immobile one was while playing a cello. I was like, “Hey, you can pick it up and carry it!” 🙂 It seems like a cello is in a nice middle ground between being a portable, personal instrument and a large and mobile enough stage prop to be interesting. Pianos are large enough to engage, but TOO large and immobile. They are dead whales on stage. 😦

I do recall though thinking to myself when I started in on viola that I did NOT want a cello because I didn’t want to play what I called “another piece of furniture.” I wish I liked high-pitched noises. (I’ve been swearing a blue streak at that stinking viola for a while now. It HURTS.)

LikeLike

Most of that immobility is just a specific tradition of playing the instrument as well as the idiosyncrasies of that tradition of playing. I’ve seen bassists using a full upright in Rockabilly or Eastern European bands dance around, under, and on top of their basses during shows, so once you get outside of the classical music or art music world (e.g. Arabic string players) there seems to be all manner of moving with the instrument as a part of the performance.

I think a piano could be an interesting instrument to dance with though it would serve more as a prop around which to dance rather than as a prop to move around with, obviously. I guess it’s all in how much you want to break out of the box of performing styles!

LikeLike